Madagascar may be a small island but it has a significant role in the world of vanilla, producing around 80% of the world’s annual vanilla bean production.

For over a century, thousands of smallholder farmers on the island of Madagascar have grown and sold the world's largest, and best, bourbon vanilla crop.

Madagascar may be a small island but it has a significant role in the world of vanilla, producing around 80% of the world’s annual vanilla bean production.

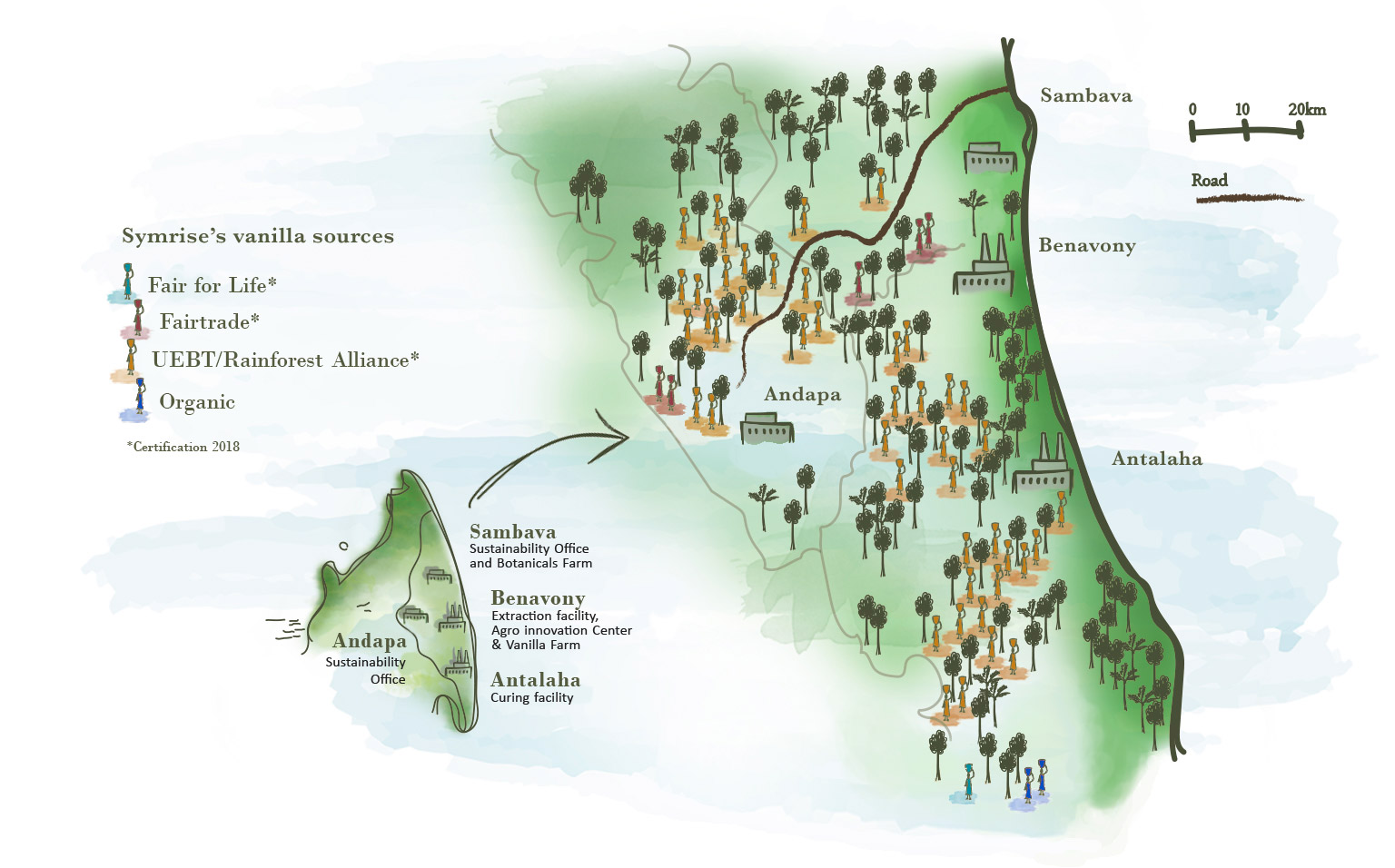

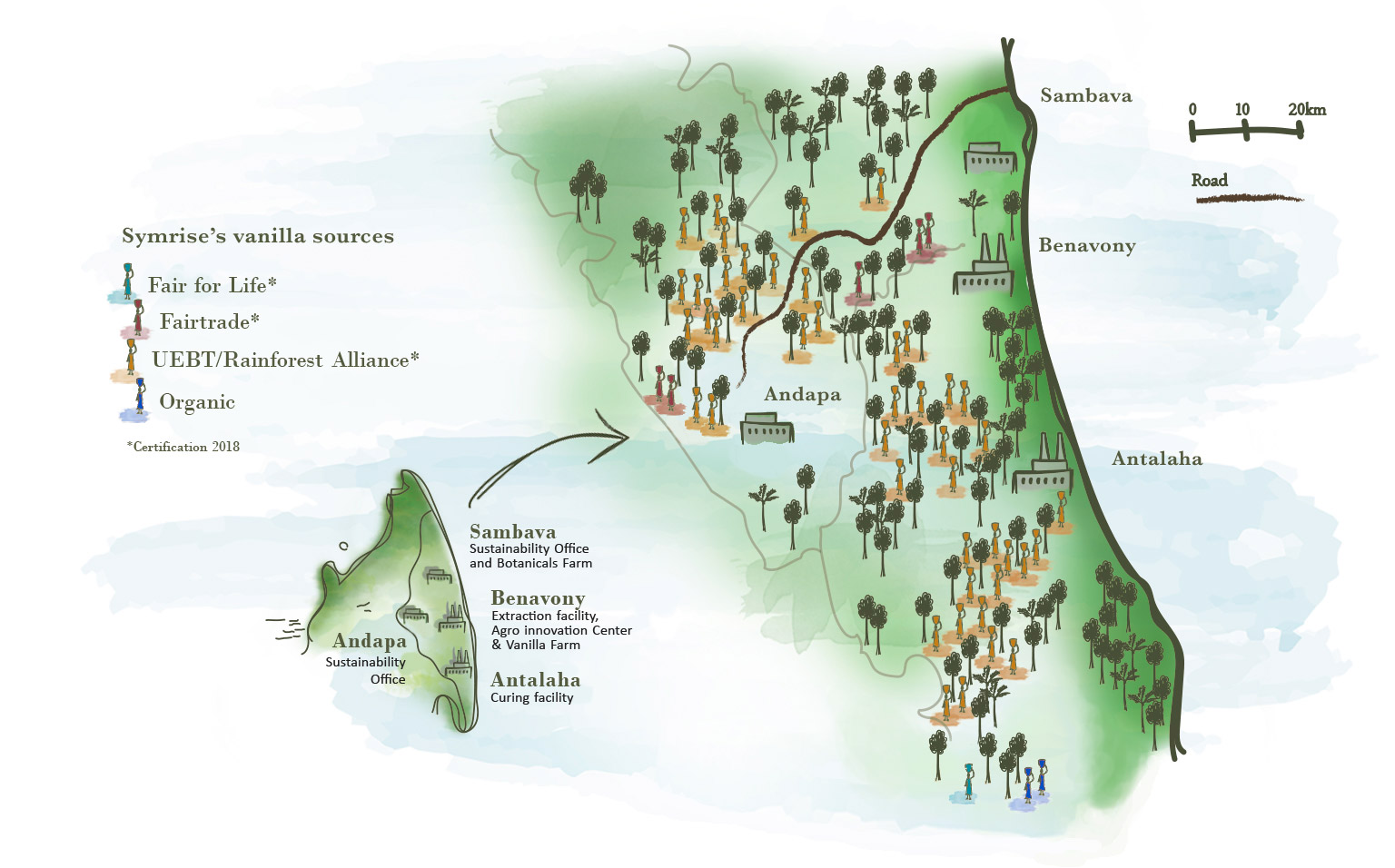

We’ve been working in the SAVA region since 2006, partnering with over 7,000 farmers across 99 villages. Today, annual harvests of around 2,000 tons of beans are still produced by skilled smallholders, pollinating the vanilla orchids by hand. As the only company in the industry with a local presence in the heart of global vanilla production, we’ve been privileged to gain deep insights into vanilla cultivation over the past decade, learning from those for whom vanilla is a major part of life and sharing ambitious goals for the communities we live and work in.

To deliver a positive impact in such complex environments, being present in the community is vital. Our facilities are set up in the heart of Madagascar’s vanilla production region to ensure we stay proactive in how we innovate and deliver positive solutions for all actors.

Creating the best possible vanilla product demands the best possible vanilla crop: working closely and sustainably with local farmers is the only way to achieve this. At Symrise, we prioritize this by offering our partners higher income, greater independence, health insurance and improved education opportunities. We also support them in protecting the environment, promoting reforestation and securing their future.

We achieve this by working with our team on the ground all year round; our tightly integrated system relies on proximity to both farmers and products. This long-term, face-to-face work allows us to gain the trust of producers. Our commitment to purchasing and sustainable development activities have a positive impact on villages, landscapes, and wider territories. As a result, we are able to initiate and guide change in practices to have the best possible quality of vanilla. Jessica, who’s responsible for our sustainable sourcing activities, is a well-known and well-liked local figure. She empowers producers' associations and is involved throughout our supply chain. “It is with people like Jessica that we build a relationship of trust and proximity”, says Laurence. For example, payments are made without intermediaries. The team is present on the ground for every negotiation, allowing us to control traceability and secure the supply chain. Our support goes beyond standard certifications, like UEBT. It is an integral part of our values and the team's convictions.

Working directly with producers on sustainable sourcing gives meaning to my work. The producers are grateful for the added value and benefits that come with our support. This is what makes me so proud of our collaboration.

A labor of love

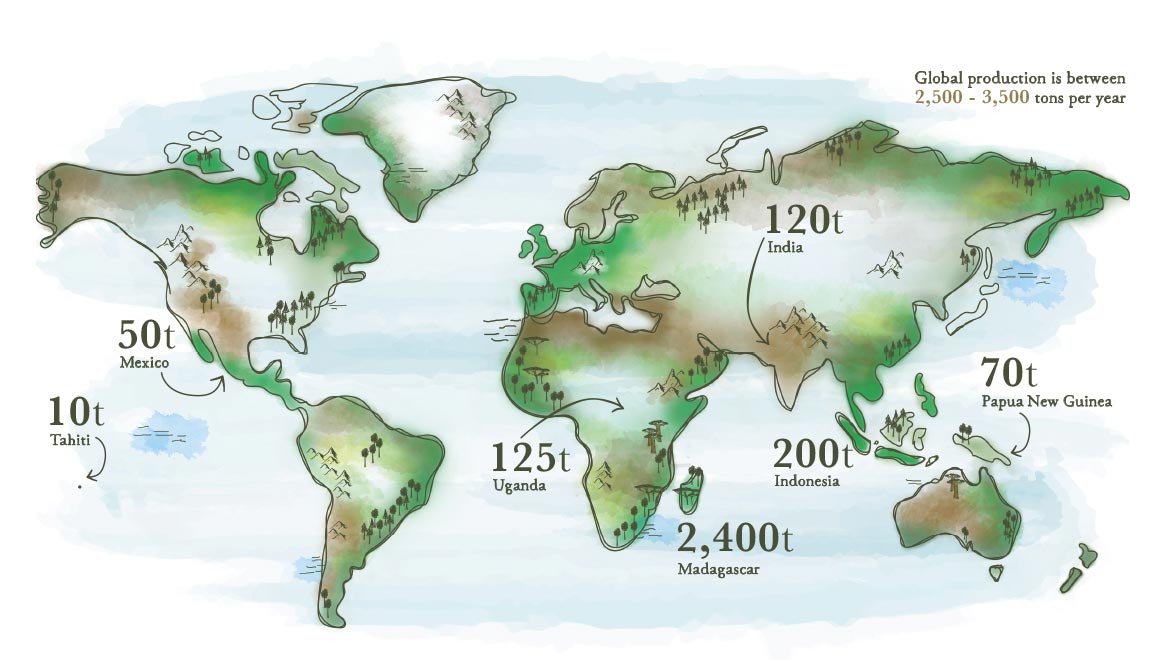

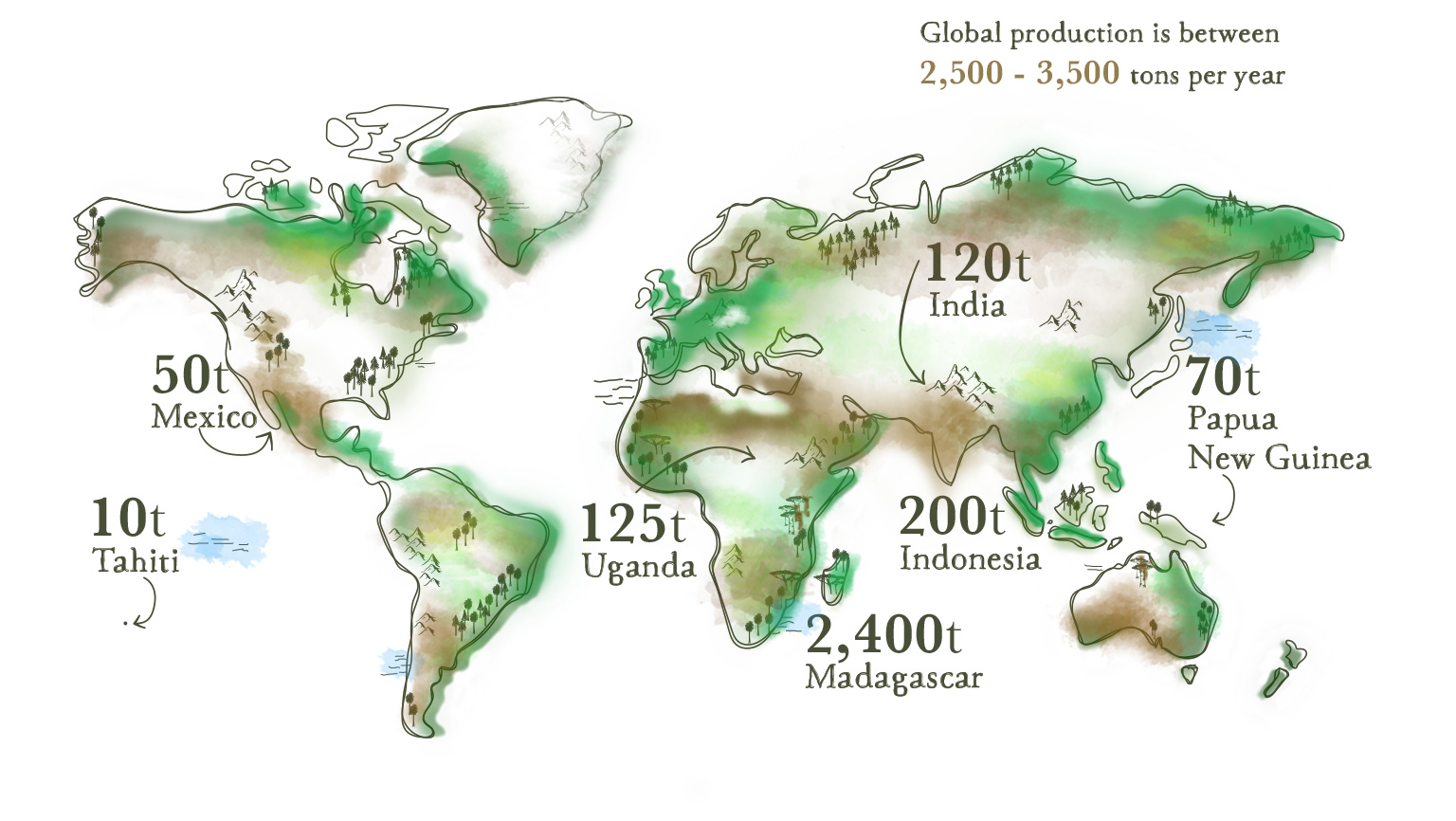

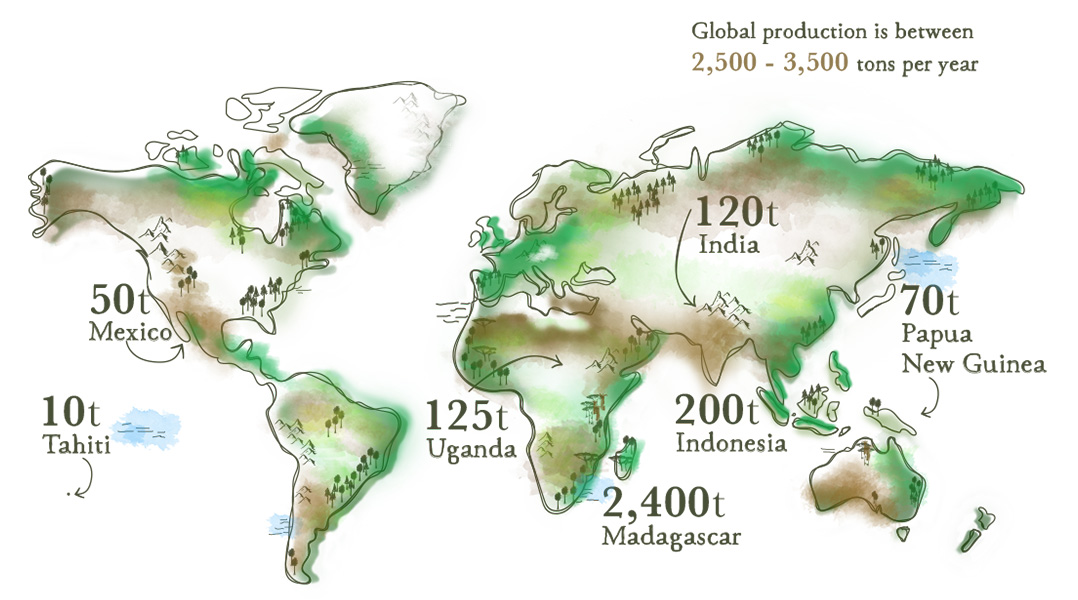

From origins in Central America where it was first cultivated by the Totanac people, today the vanilla orchid is grown in tropical climates around the world. Pollinated by hand everywhere except in Mexico, and with flowers that may only be open for one day, cultivation is highly labor-intensive.

From Mexico to India, skilled and dedicated farmers produce an annual global vanilla harvest of between 2,500 to 3,500 tons, but by far the largest crop comes from Madagascar.

Across Madagascar, around 70,000 farmers plant, pollinate, care for and harvest vanilla orchid plants - most of them in the SAVA region.

The north eastern SAVA region of Madagascar is where almost all of the island’s vanilla crop is cultivated – it’s also home to our operations here in Madagascar.

600 blossoms need to be pollinated by hand to produce 6 kg of green beans

Around 6kg of green vanilla beans are needed to produce 1kg of black beans

From 1kg of black beans, we produce 10 liters of concentrated vanilla extract

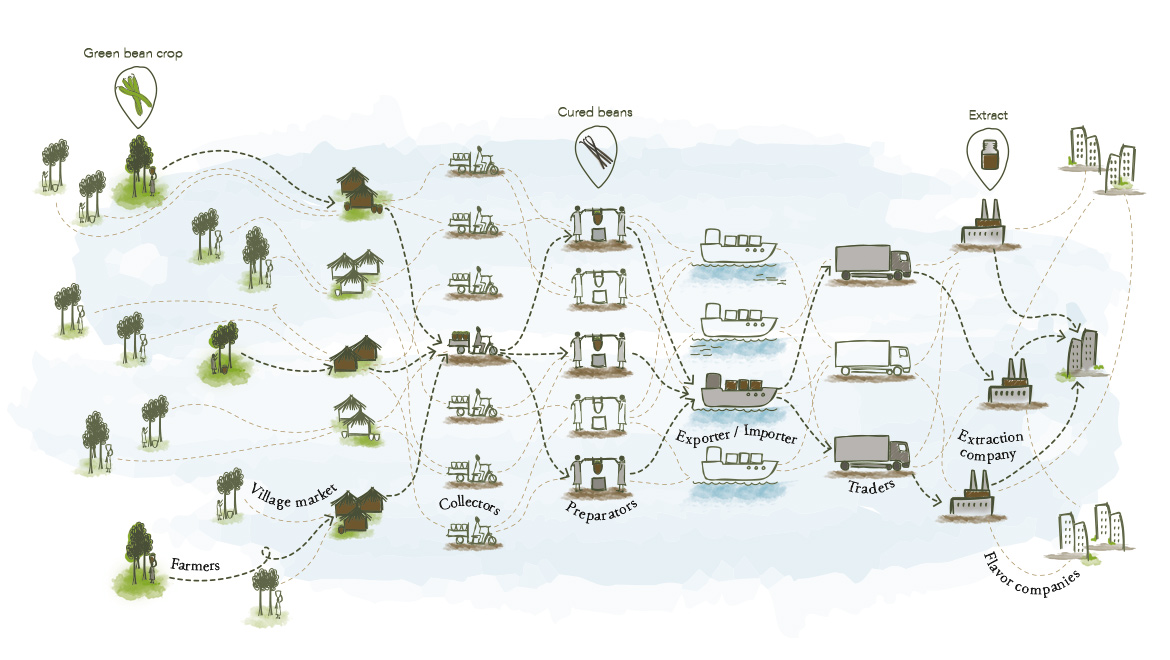

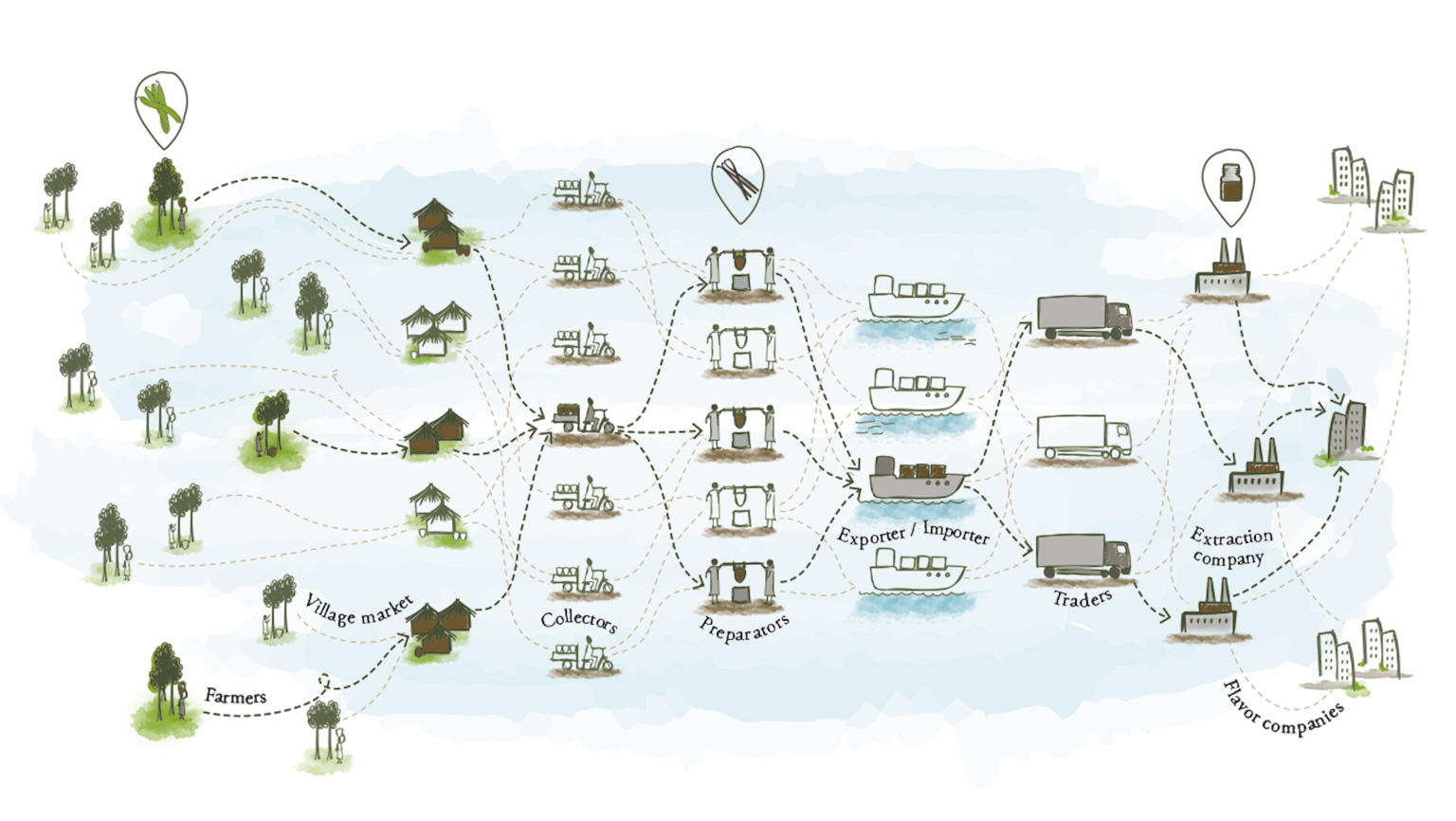

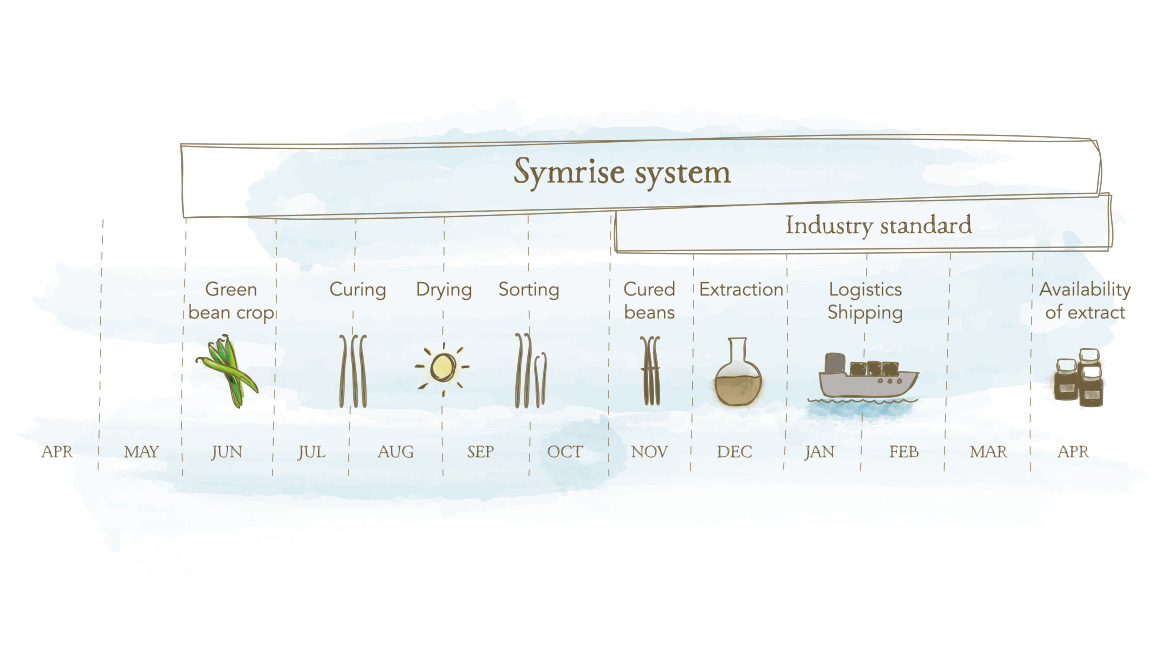

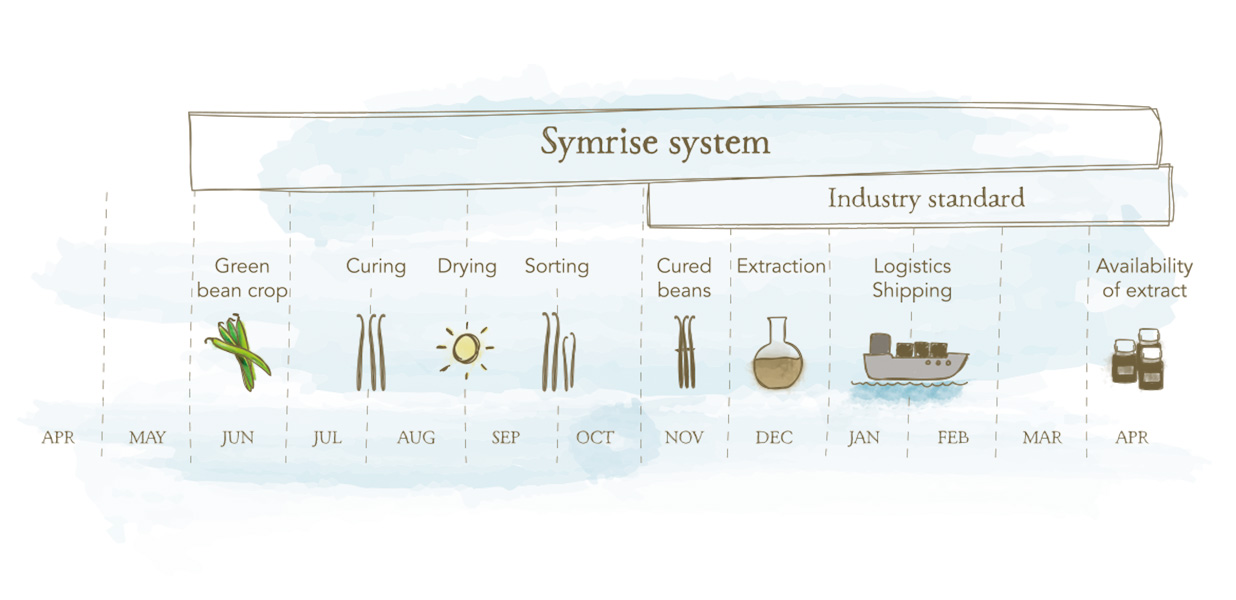

The traditional supply chain

For decades, green beans harvested by famers have been sold at markets to intermediate traders, who then sell the vanilla on to processors and refiners. These businesses then supply international flavor companies, making tracing the supply chain of the vanilla beans almost impossible.

While the traditional system has survived for many years, it doesn’t provide the traceability, consistency of supply, and security for the farmers that a truly sustainable model can.

Vanilla is one of the most labor-intensive crops in the world: in Madagascar, vanilla is nearly all grown by independent smallholder farmers, who live in small, dispersed villages and hand-pollinate their crop. Farmers bring their harvested green beans to local markets, where they’re bought by intermediaries to be sold on to processors and refiners.

This model has many links, often making it impossible to trace the origin of any given batch of beans. This can result in an inconsistent supply and little financial security for farmers. Uncertainty and the need for cash can put pressure on farmers to harvest their beans early, before they’ve fully matured, impacting vanilla quality as well as the farmers for who vanilla is often the only source of income.

Thanks to its many links, tracing the origin of a particular batch of vanilla beans through the traditional sourcing model is almost impossible.

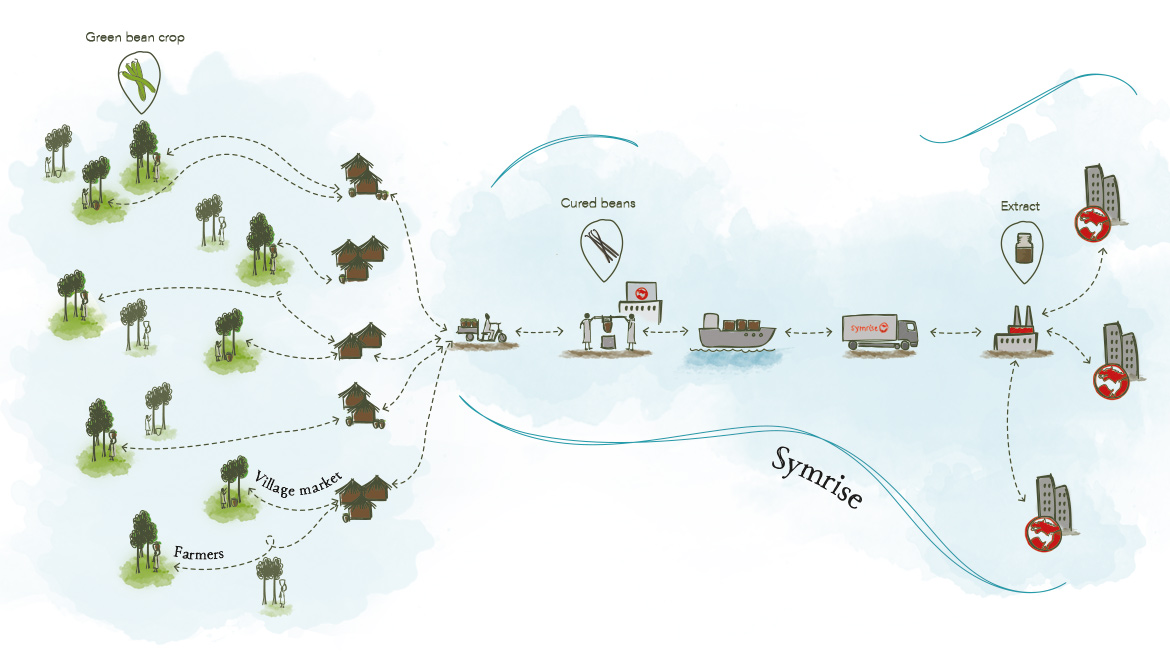

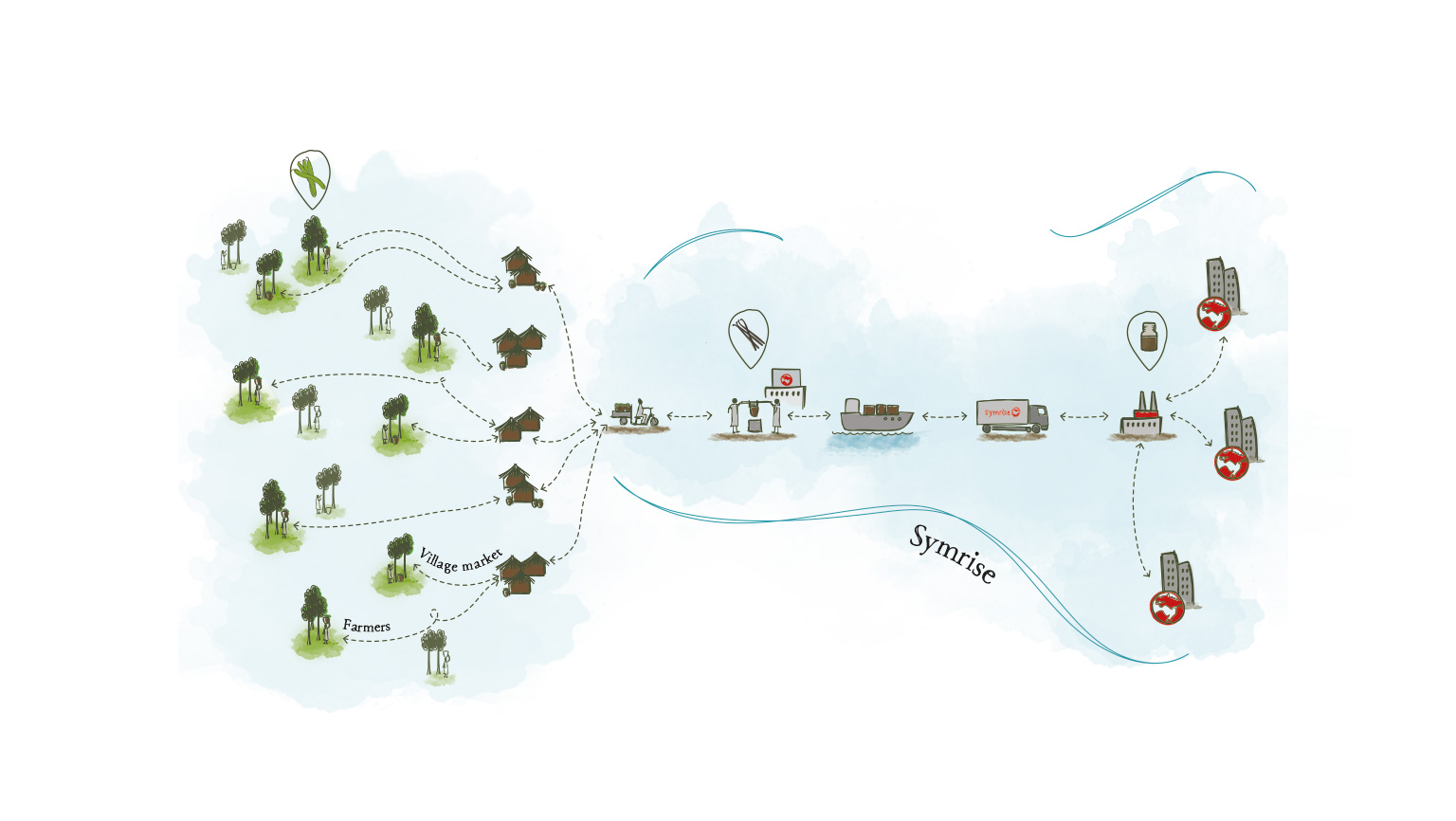

To maximise the positive sustainable impact of our value chain, we go direct to the people who grow the vanilla crop – the farmers.

Transformational change begins with an idea. Our idea was to create a better way of sourcing vanilla – for us and our customers, for the farmers, and for the environment – by ensuring the vanilla we buy is sustainable. That doesn’t mean we’re replacing the smallholder farming system that has produced high quality vanilla for decades. Instead, We’re working closely with farmers and local communities to improve cultivation practices and contribute to strengthening the infrastructure of communities themselves.

First, we had to persuade others that this idea was the right one for them. Farmers who were entirely reliant on the income provided by their vanilla beans and who had known the traditional supply chain all their lives, needed to believe in us and in our idea. Already insecure and financially vulnerable, they couldn’t afford to take a risk with their livelihoods. Trust was essential.

So we began the process of communication and collaboration that’s been the foundation of all our work in Madagascar. We worked to understand the current supply chain, the farmers and their needs and concerns. We engaged with intermediaries who bought beans in local markets, and employed them as supervisors and inspectors. We used technology to map where vanilla was grown and worked with farmers to assess the best ways to improve cultivation.

Our direct relationship with farmers and their co-operatives provides the product traceability which is essential to achieving a sustainable integrated supply chain

Since we began our work in Madagascar in 2006, we’ve been able to show an increasing number of farmers the benefits of being part of an integrated, sustainable supply chain – and they’ve chosen to work with us in their thousands.

We think this is partly because our work is about more than securing a sustainable supply chain. We’re working closely with farmers and local communities to improve cultivation practices. One of the key elements of this is training farmers in things like crop diversification and soil management. By helping farmers maintain their plots year round and grow a wider range of crops, we can help them improve their financial security – a major issue when you rely on just one crop for your entire income.

We promote inclusive and regenerative agriculture as well as gentle processes of the natural ingredients we cultivate to deliver the best quality and secure sourcing. We share this value by reinvesting in the SAVA region for the benefits of our precious colleagues and partners engaged in the supply chain.

Every day, across the SAVA region, our team works with farmers to grow premium bourbon vanilla sustainably.

over 7,000 small-scale farmers produce vanilla for Symrise

We work with farmers in 99 villages across Madagascar

Around 30,000 people benefit from this cooperation

By bike, by foot, by boat, our team visits some of the

remotest villages in Madagascar to train, guide and

audit our farmers.

No farm is too far.

Our committed team works with passion, ready to face any challenge in the field. You have to experience the vanilla industry from the inside to understand its complexity and to be able to provide solutions. Being a player in the supply chain at the source, where the first link in the chain begins – seeing and experiencing the daily challenges of producers every month of the year – reinforces the commitment of the team on the ground to provide solutions that are not limited to the product itself, but also take into account the environment of vanilla production as a whole. Our holistic approach also enables us to prevent and manage risks.

In recent years, we have been working on the transfer of intergenerational skills. Today, there are more young people and women recruited, elected and involved in our supply chain, who are gradually gaining the long-term trust of the region’s producers.

We value every producer’s experience in agricultural practice as well as the knowledge acquired by our rural advisors to bring continuous improvement to the management of our database. The training and coaching for our internal controllers allow us to have competent, competitive and local human resources in the local job market. Mutual trust with local communities also allows us to work together with producers loyal to our sustainable supply system. We ensure a permanent presence of our supply and respect our commitments to producers.

Sustainable accreditation

Farmers can maximize their income by gaining sustainable accreditation for their vanilla crop – which also meets our customers’ brand needs.

Fair for Life focused on responsible supply chain by implementing good economic, social and environmental practices.

Location is everything when farming vanilla. Too much sunlight can ruin everything, soil moisture needs to be perfect and you need the right amount of tree coverage to provide shade for the delicate vanilla plants. But finding a plot is just the start. Farmers then need to thin plots out, plant ‘tutor trees’ in the dry season between which the evergreen vanilla vines can grow, and when the rain comes, plant the vanilla-seedlings.

Once planted, there is a little time to rest as growing vanilla is a patient process as it will be three years before the first flowers appear. That said, plots need cleaning up to three times a year, and new vanilla tendrils, which appear around tw0 weeks after planting, need placing around tutor trees.

Experienced farmers can pollinate between 1,000 and 2,000 blossoms a morning. Eight to nine months later, the first vanilla beans are ready to be harvested.

Tsarafidy Rasana has dedicated many years to cultivating his remote vanilla farm, which is more than two hours walk from his home through the steeply rising forest. At first glance, Tsarafidy's small vanilla plot looks no different to the forest around it. But his vanilla plants have wrapped their delicate tendrils around the surrounding trees, where he tends, pollinates the flowers and harvests the beans, all by hand. Tsarafidy's plot is typical: tens of thousands of small-scale farmers cultivate the ‘Queen of Spices’ in small pockets of land across Madagascar. We work directly with over 7,000 farmers like Tsarafidy.

Frankline works directly with farmers to improve their vanilla harvest using sustainable farming methods. She knows vanilla, the farmers who grow it and the local terrain like the back of her hand. Frankline is part of our advisor team - each of our advisors works directly with the farmers across numerous villages, often travelling for several hours to reach the remote farms where they work. One topic Frankline is focusing on is working with the farmers to promote good sustainable agricultural practices without damaging the environment rich in biodiversity.

By showing farmers how to grow a more diverse range of crops, we can grow on steep slopes, restore nutrients to the soil and prevent erosion.

Fidèle Makany, elected by the village, meticulously records the location and plants of his village’s farms as part of our commitment to sustainable farming. Fidèle is an 'internal controller' - a vital part of our effort to improve both the livelihoods of farmers and the traceability and sustainability of their vanilla.

Working with trusted inspectors like Fidèle, we have mapped the location of the farmers' plots, as well as the course of rivers, areas affected by slash-and-burn practices, rice fields and foot paths. These maps describe the flora and fauna in each area, the volumes harvested, the condition of the soil and the plants, the vanilla harvest of the past years and the progress of other agricultural products.

I find it very important to leave a healthy environment behind for my children. We need to watch out that we do not destroy our soil.

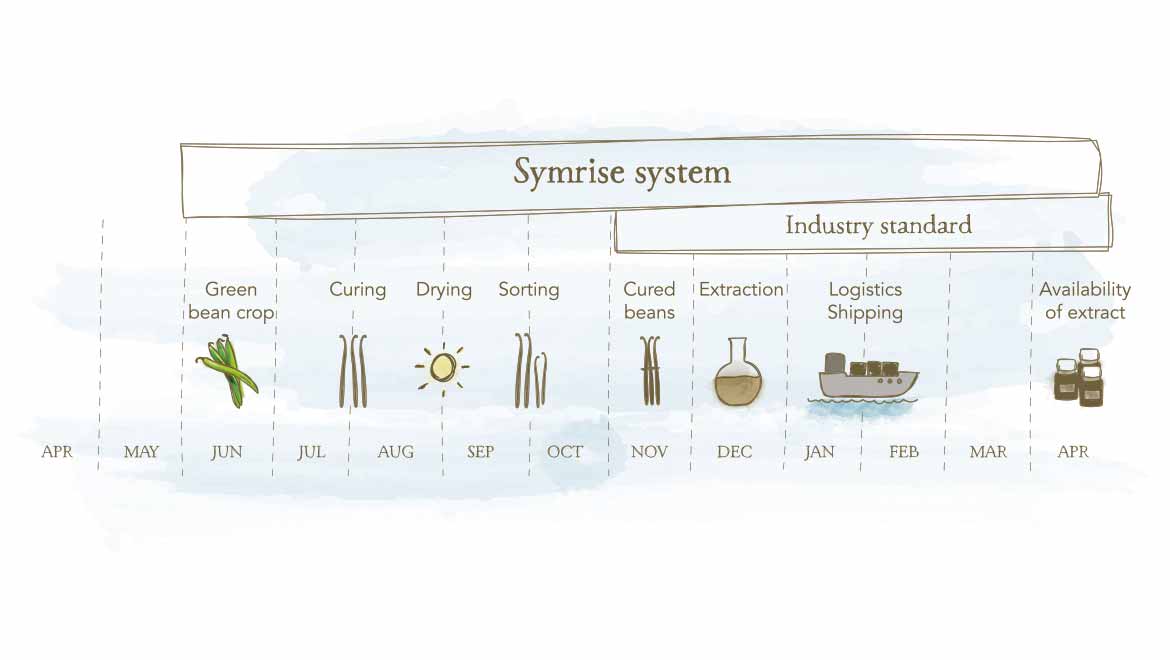

Turning green vanilla beans into the highly aromatic black beans that we know and love is as skilled and complex as making wine. And like good wine-making, it relies on a blend of artisanal skill and scientific know-how, that is called the wonder of curing.

curing, expertly controlled

There's no room for improvisation with a process as intricate as curing, which demands continuous expert control.

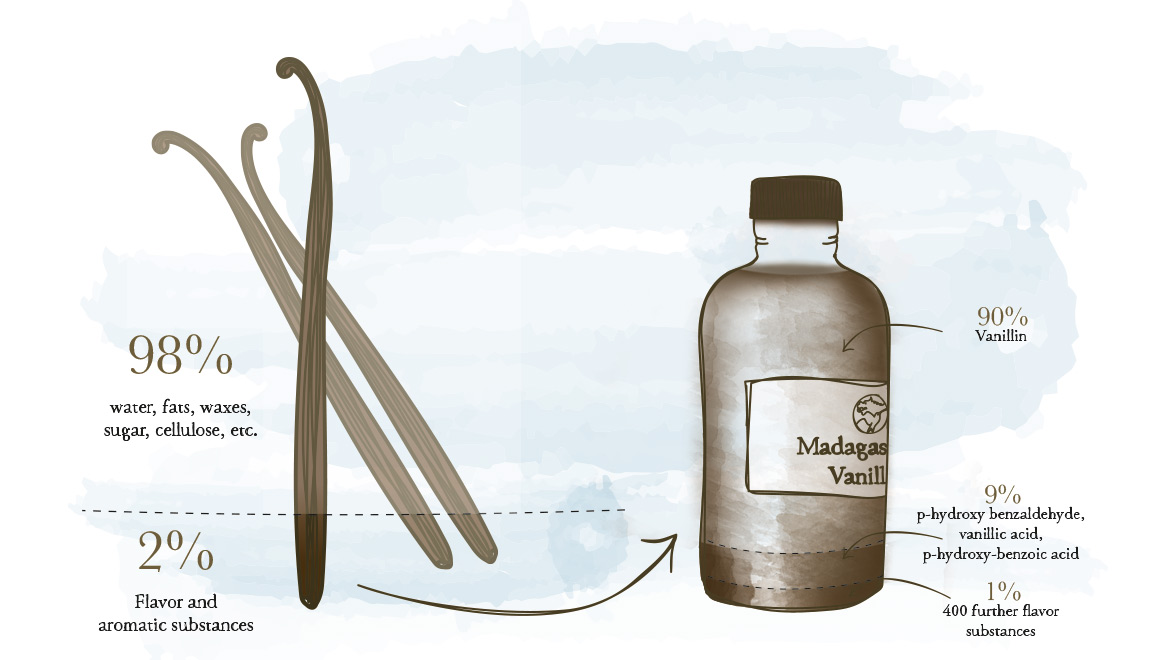

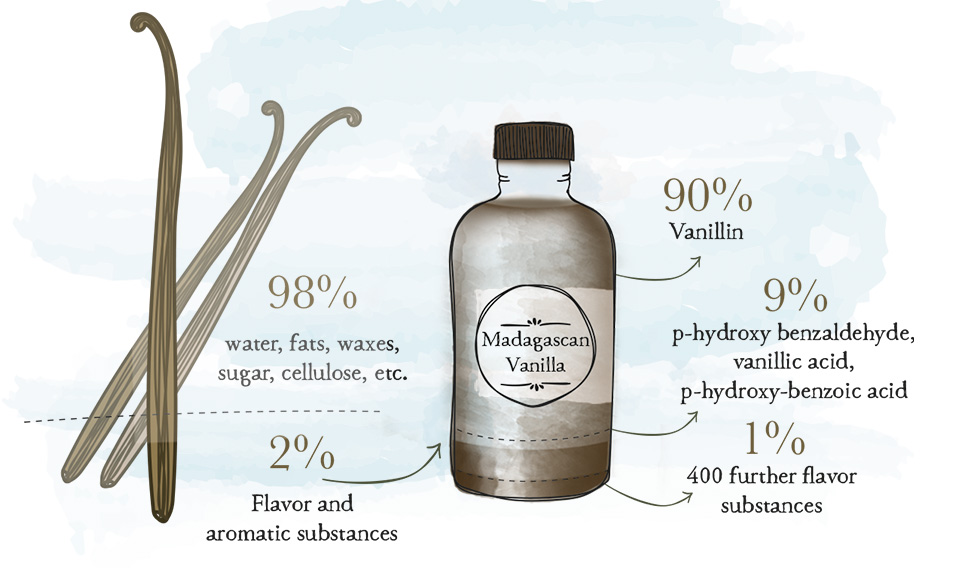

Natural vanilla has one of the most complex flavors in the world. Curing releases this natural flavor, vanillin, by using enzymes to split open the glucovanillin present in the beans.

Hand curing vanilla beans is an intricate, detailed process that takes months. Everything has to be just right – from purchasing the right beans, through more than 50 process and quality-control stages, to choosing the right packaging. We’ve mastered this business using traditional methods, a great deal of expertise and decades of experience.

Curing requires painstaking attention to detail. It begins at the moment the green bean is purchased, when villagers bring their crop for sale on a day specified by the Malagasy government in order to ensure maximum ripeness. Every bean is inspected for quality, which is no easy feat at hectic markets where thousands of beans are being sold. The beans are then sorted according to size and color, heated in water, packed into crates wrapped in cotton blankets to ‘sweat’, before they’re finally dried under the Malagasy sun.

By the time the beans are ready to be dried, they’ve been handled about 50 times. The sense of touch plays a decisive role in checking their condition and deciding when the vanilla is fully ripened. More than anything, we need to feel the moisture and elasticity with our fingers.

It’s the magic of curing that transforms the green vanilla beans into the aromatic black beans used in products across the world. But magic takes time: the whole curing process can last months.

Vanilla is one of the most complex spices in the world, made up of 400 – 500 individual aromatic components, all of which have an impact on the beans’ final taste and aroma.

Knowledge, experience and expertise

Between them the team at our curing plant share many centuries of experience. From Manajara, our weatherman, to Maro, one of our highly experienced inspectors, they ensure our vanilla is of the highest quality year after year.

Mananjara is a short range meteorologist, vital to ensuring the fermenting vanilla beans aren’t ruined by the rain as they dry in the sun. To ensure the best possible product, all the stages in the curing process have to be spot on. This means, among other things, that the vanilla needs to ripen in the sun for just the right amount of time, without getting wet. This makes Mananjara one of the key people in the whole curing process.

When Mananjara says that rain is coming, you had better believe it is going to rain. We have complete trust in him. He is extremely important to us.

After many years working in the drying team, Soazery is now one of the sorters who meticulously examine and sort the vanilla beans. Seated at a long table among dozens of colleagues, Soazery Sina Olivette deftly sorts vanilla beans into bundles. “I pay attention to the thickness, whether they are split open at the ends or have any color variations,” she explains. “There is no margin for error in this work if you are going to achieve the highest quality.”

Maro is one of the team of quality control inspectors who draw on their years of experience to analyse the quality of the beans, and to assess how they should be treated to achieve perfection.

Maro fans out a bundle of vanilla and holds it directly under his nose. He sniffs, bending some of the beans sideways, then sniffs again. “Just as it should be,” he says, and places the bundle into a sack. Like a wine connoisseur, Maro has a whole language to describe the quality of beans – and his sharp eye doesn’t miss a thing. He and his equally experienced colleagues make the final, decisive checks on the vanilla beans at our curing facilities – the last of many stages in our quality control process.

Maro’s face is covered in small black dots from the small vanilla seeds that stick to the beans – evidence of the work he loves.